This show is all about desire and possession. It explores how beautiful, curious and engaging objects were made, marketed, acquired, personalized and valued. Some objects shown here are undoubtedly masterpieces: works of dazzling design and innovative skill, long-prized as highlights of the Museum’s collection; others are more ordinary. The purpose of this exhibition is to move beyond conventional appraisals of artistic or monetary worth to appreciate how objects were crafted and what they were made from, and how possessions took on changing meanings for individual owners.

The Renaissance to the Enlightenment period is a long one (about 1400 to about 1800), which saw profound changes in the production and availability of goods. Over this time, we can chart the emergence of new luxuries and technological innovations, the importation and imitation of foreign artefacts such as porcelain or calico, the domestication of new world substances like chocolate or tobacco, and the first stirrings of mass production that would transform the European home.

The objects in this new material world created new visual realities, and changed how people felt about themselves and others. Despite the rapid increase in the availability of non-essential goods, objects from this period were often charged with emotional significance and inscribed with sentimental value. Some of the things on display are named and dated so as to commemorate an important event such as a marriage or a death. Others show signs of persistent wear and tear and deliberate mending. There are home-made items, painstakingly created and handed down from one generation to the next. And there are showy pieces which flaunt the tastes, aspirations and fantasies of their past owners. Of course, we cannot always reconstruct the hidden history of an object; many of these treasures still hold their secrets tight.

I: A New World of Goods

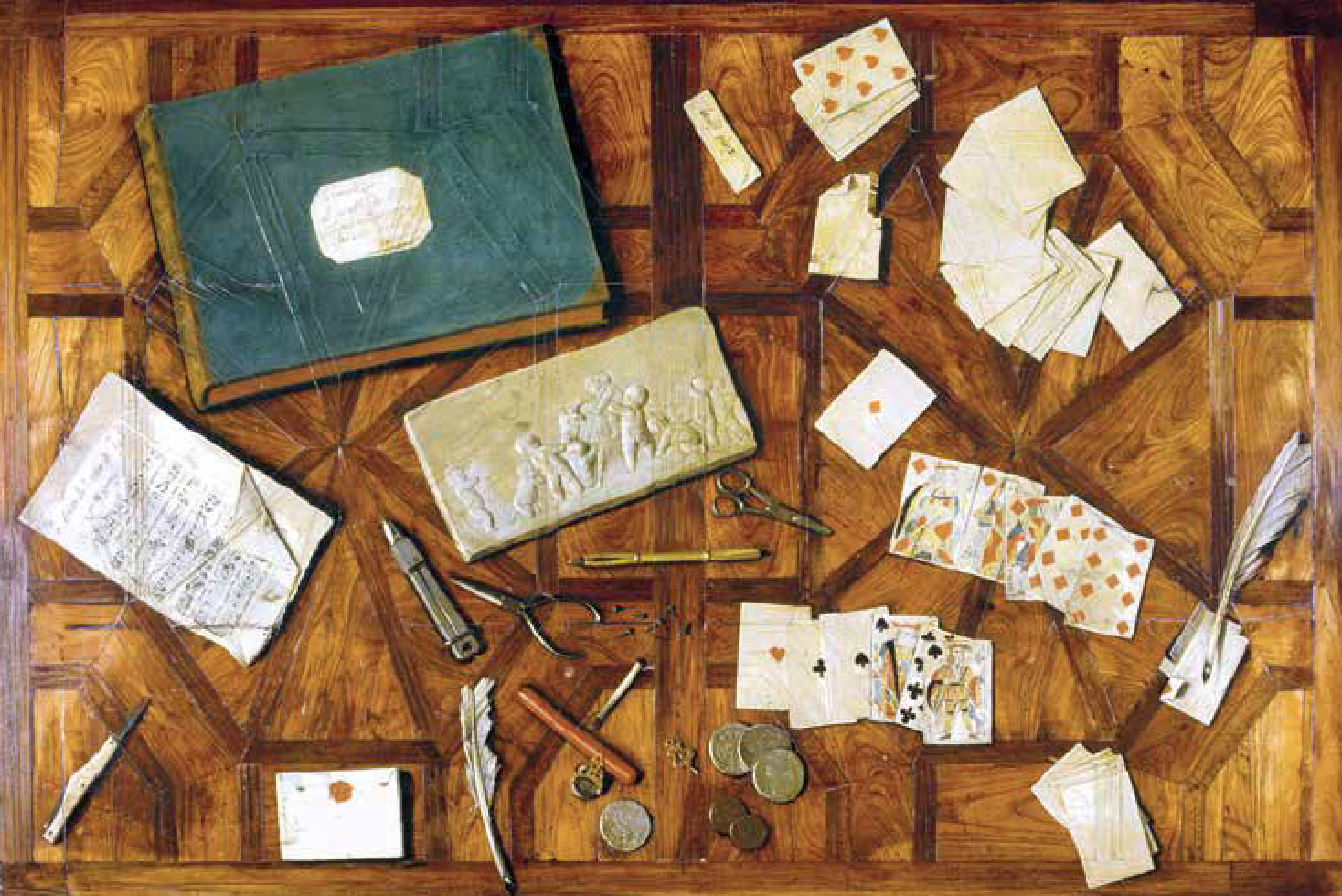

The Renaissance witnessed an explosion of goods. Lists of household possessions, carefully recorded by scribes and preserved to this day, give a sense of the accumulated clutter in prosperous homes. Such inventories describe elaborate dinner services, glassware, furniture, linen, clothes, jewellery, ornaments and books. Equally striking is the presence of highly specialized items, such as hand-warmers or flower vases, often created to be beautiful as well as functional.

The great variety of objects in European homes testifies to new expectations of comfort, convenience, pleasure and taste. Here we find the new world of goods that Europeans discovered throughout the period: the age before industrialization and mass production, when non-essential commodities nevertheless became widely available across the social spectrum. While local craftsmen honed their skills to produce the innovative and intricate objects demanded by their clients, exotic foreign goods also entered the market. In turn, high-quality objects made at home were influenced, formally and stylistically, by global imports. The treasures displayed in this section give a taste of this astonishing period of innovation and experimentation.

II: Desiring and Acquiring Things

The Renaissance to Enlightenment period is often seen as an age of acquisitiveness, when Europeans tasted the pleasures of shopping for the first time. The reality of that experience was, however, a far cry from the sanitized world of today’s supermarkets and department stores. Buying and selling were activities subject to stern moral judgment and anxiety; fears of cheating and deception abound in literary accounts. Nor was it necessary to go to a shop in order to shop. Some of the treasured possessions exhibited here were commissioned directly from the maker; others were acquired from street vendors or markets.

In the eighteenth century, shopping became more than simply acquiring goods. It was a pastime and leisure activity, especially for the rising middling classes. Shops appeared in many British and continental European cities. They replaced market stalls and itinerant pedlars, offering a new experience for consumers increasingly allured by the goods displayed in their windows. At the same time, street sellers were the subjects of printed illustrations and expensive porcelain figures. Shopkeepers were also at the forefront of marketing innovation. They advertised their wares and services in newspapers and through trade cards and bill heads on customer receipts.

III: The Irresistible

Antonio de Pereda’s painting Still Life with an Ebony Chest shows a mid-seventeenth-century Spanish vision of the irresistible: ebony from Africa, porcelain from China, chocolate and sugar from America, and lustreware from Valencia. The value of these enticing commodities lay not only with their rarity but also with their potential to generate pleasure. While ongoing anxieties about luxury and consumption did not disappear, Pereda’s image offers a meditation on the joys of living in ‘the here and now’.

The irresistible was inextricably linked to the expansion of Europe and the idea of the exotic, which changed constantly in response to the exploration of ‘new’ worlds. The Medici court in early Renaissance Florence desired the colourful and stylized designs of Iznik pottery and was, later on, the first European connoisseur of Chinese porcelain. Contact with America not only brought chocolate and sugar but also encouraged a new interest in the natural wonders of the New World. By the end of the eighteenth century, tobacco, chocolate, tea and coffee had all been ‘domesticated’ by Europeans. New objects, new behaviours and new social spaces were created for and by the consumption of these novel stimulants.

IV: The Fashionable Body

The visual arts often dominate our sense of the Renaissance. Yet this cultural movement became visible to many through a new world of fashion. Tailoring was transformed by new materials and refined techniques of cutting and sewing, as well as by the demand for a tighter fit, particularly for men’s clothing. Enterprising merchants created larger markets for fashion innovations and ‘chic’ accessories. Artistic representations of the clothed body proliferated as never before. Mirrors enticed people to experiment with their appearance, as they caught sight of their reflections in looking-glasses on walls, or in small portable mirrors designed to be carried on the body.

This new type of consumption and aesthetic appreciation depended on the assemblage of a panoply of wearable goods from clothing and armour to accessories like hats, hair-pieces, feathers, toothpicks, rings, gloves, purses and shoes, which brought self-display to life. The tiny honestone portrait from the 1520s shows a woman at the height of fashion with a bonnet perched on her head. In turn, the earthenware male figure of 1606 sports an expensive modish slashed suit with belt, buttons and a flamboyant feathered hat. Even the style of facial hair could codify people and establish identities.

V: At Home and On Display

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

As Renaissance shoppers acquired more ‘stuff’, even ordinary homes became places of display, and new types of furniture evolved to store and show off the family treasures. During the period covered by this exhibition, traditional chests were replaced with front-opening cupboards, dressers and sideboards – versatile props on which ornamental items could be positioned. Meanwhile, cabinets containing small drawers allowed collectors to order their most precious objects, keep them safe under lock and key, and then draw them out to show selected visitors.

© National Trust

By the eighteenth century, technological changes, the expansion of global trade networks, and the growth of European markets had broadened the opportunities for buying and displaying goods in the home to a much wider group of people. Tea services were laid out and admired on sideboards, inkstands on desks, vases on mantelpieces, and scent-bottles and patch boxes on dressers. A whole range of ornamental porcelain items was available as well as equally coveted imitations in cheaper earthenware. The sub-division of interiors into specialized spaces resulted in new kinds of furniture such as the tea-table or secrétaire (‘writing desk for ladies’) used both to display fashionable objects and to hide its owner’s secrets.